In my previous entry, I said that economists approach the question of whether there ought to be public subsidy for the arts based on the idea of externalities: are there people who benefit from someone else’s attending a performance in ways outside of market implications?

To my mind the strongest case for such externalities is concern for future generations. I am not writing here about what arts policy towards children ought to look like (I’ll get to that later in the series). Let’s think in terms of future generations of grown-ups, yet to be born.

There are many good things going on in the arts that I do not attend, and that I am unlikely to attend, either because there is not much of it going on in my neck of the woods (especially contemporary art) or because it is something I just don’t know enough about to really get something from it (modern dance, for example). But I want artists to keep having the chance to do interesting work, and they need audiences for that, and if I am not a part of that audience I am glad that someone else is a part of that audience. I want artists and audiences (and critics, come to that) to keep art alive so that generations yet unborn will inherit something more interesting from their culture than mere amusements. If some of my taxes go to helping make that happen, I am pleased about that.

I don’t take it for granted that the future of culture will work out just fine. Here is Will MacAskill in What We Owe the Future:

Because art is so subjective, it is nigh-on impossible to assess trends in artistic accomplishment, but one often neglected factor is that, because of our sheer numbers, the artistic output of our species has increased dramatically: a higher population means more artists. And the artistic capacity of the population has, in some respects, greatly increased because of rising literacy and rising wealth: a more literate population has more writers, and the fewer people there are in dire poverty, the more artists there will be. In light of these considerations, it is likely that art has progressively reached new heights over time and will continue to do so at least for the next hundred years. The same applies to other non-wellbeing goods. The more people there are and the higher living standards there are, the more likely it is that there will be individuals, like Usain Bolt, Margaret Atwood, or Maryam Mirzakhani, who go on to achieve great things.

Well, no, I don’t think so. Yes, there might be more people born with the mathematical genius of Mirzakhani, but they will only have a chance to exercise that genius in a world that values knowledge and advancement in science. Great writers can only become great where there is a readership that can appreciate its greatness. Otherwise, we simply have a greater number of mute inglorious Milton’s. Have we had a steady increase in artistic “output” during the last century? Sure, I suppose. “Progressively reached new heights, and will continue to do so at least for the next hundred years”? I have questions.

That new restaurant in town with one hundred and sixty-seven dishes on the menu is actually not very good. A really big airport bookstore still only carries airport bookstore books, just more of them.

But the case for an externality based on concerns that future generations have a living and valuable cultural inheritance comes up against some of the same issues as with the economics of other possible externalities: (1) it depends upon people actually feeling this concern, not just that hypothetically they might, and (2) someone has to decide what things are most important to maintain, and what things can just be left to their own market devices, based on what they think is the scale and scope of current generations’ preferences over this matter, and (3) when that choice has been made, then there has to be a practical funding mechanism that is directed to that end.

You don’t have to buy in to the economic method to think that “future generations” is the best case for public funding for the arts.

An alternative to the economic approach is to think in terms of fairness. Our current generation was born with a cultural inheritance, one that we could enjoy, and that gave our artists inspiration for making new works. If we think that this cultural inheritance is a “primary good” - one that ought to be as equally shared as possible - then we owe to future generations the preservation of great works, and great artistic traditions. This is how Ronald Dworkin is able to answer “Yes” to the question “Can a Liberal State Support Art?”, an essay in his A Matter of Principle (we will get to why John Rawls answered “No” to that question later in this series).

Here is an excerpt from Dworkin (adapted from a talk recorded in the Columbia Journal of Art and the Law (1985):

My suggestion is this. We should identify the structural aspects of our general culture as themselves worthy of attention. We should try to define a rich cultural structure, one that multiplies distinct possibilities or opportunities of value, and count ourselves trustees for protecting the richness of our culture for those who will live their lives in it after us. We cannot say that in so doing we will give them more pleasure, or provide a world they prefer as against alternative worlds we could otherwise create. That is the language of the economic approach, and it is unavailable here. We can however insist - how can we deny this? - that it is better for people to have complexity and depth in the forms of life open to them, and then pause to see whether, if we act on that principle, we are open to any objection of elitism or paternalism.

Please let me retell my story, now concentrating on the structure of culture - the possibilities it allows - rather than on discrete works or occasions of art. The center of a community's cultural structure is its shared language. A language is neither a private nor a public good as these are technically defined; it is inherently social, as these are not, and, as a whole, it generates our ways of valuing and so is not itself an object of valuation. But language has formal similarities to what we called, earlier, a mixed public good. Someone can exclude others, by relatively inexpensive means, from what he writes or says on any particular occasion. People cannot, however, be excluded from the language as a whole, or at least it would be perverse to exclude them, because from the point of view of those who use a language free riders are better than no riders. And the private transactions in language - the occasions of private or controlled speech - collectively determine what the shared language is. The books that we write and read, the education we provide and receive, the millions of other daily transactions in language we conduct, many of them commercial, all of these in the long run determine what language we have. We are all beneficiaries or victims, in the end, of what is done to the language we share.

We know languages can diminish, that some are richer and better than others. It barely makes sense … to say that people in later generations would prefer not to have had their language diminished in some particular way, by losing some particular structural opportunity. They would lack the vocabulary in which to express, that is to say have, that regret. Nor does it make much more sense even to say that they would prefer to have a language richer in opportunities than they have. No one can want opportunities who has no idea what these are opportunities of. Nevertheless, it is perfectly sensible for us to say that they would be worse off were their language to lack opportunities ours offers. Of course, in saying this, we claim to know what is in their interests, what would make their lives better lives.

I find this quite persuasive. Dworkin is not an economist - he explicitly rejects economism as a way of thinking about culture - and as such his solution is not about what preferences we might have for how to allocate our own scarce resources. He is also not a paternalist - “eat your opera, it’s good for you!” - but rather just wants future generations to have possibilities. A liberal order, in which people develop their own ideas about what is worthwhile in life, requires that people have a language and culture that permits conceiving of what is worthwhile. An impoverished culture confines our imaginations. This is also the basis of why Will Kymlicka thinks we need to allow cultural minorities the chance to preserve and live their own cultural inheritance, that they too can have some basis for forming their ideas of the good.

That said, in practical terms the economist who thinks there are externalities from thinking about future generations and the liberal egalitarian who thinks there is an obligation to preserve a rich language and culture for future generations have similar challenges: how do we go about this? What to directly support through public policy, and what to leave be? Who makes these decisions?

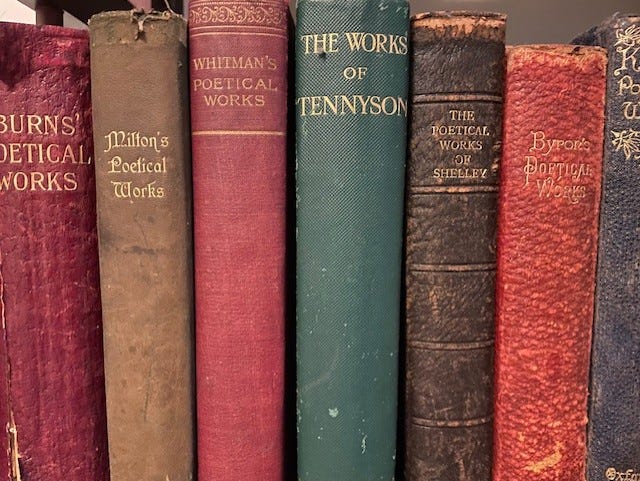

Coda: The photo at the top of this post is from my own bookshelf; these books were prizes that my grandmother and her sister, my great aunt, won when they were schoolgirls in Scotland, and then passed along to my father, and then to me, and eventually to my own children. This is not a Bourdieu story about cultural capital - I didn’t grow up in a house where anyone could say we had a thing that could be “exchanged” for monetary capital. But there has been an unstated but common assumption amongst us that it has been important to preserve these poems.

I also cited mute inglorious Miltons in this context, but closer to the original. Billions of children never get the opportunity to create, and increasing the population, without improving health and education, will only produce more

https://johnquigginblog.substack.com/p/mute-inglorious-miltons

I agree completely with this -- I will be curious about the later discussion of Rawls, there are ways in which the details can get thorny but I think the call to sustain a rich culture for future generations is compelling.

I would add the (obvious) extension of your point, that this also requires opportunities for participation. I occasionally mention Jane Alexander's book about her time running the NEA and one of the things I appreciate about it is that she defends both some of the controversial avant-garde art and also the NEA support for local arts programs. She talks about the importance of local theater and summer stock programs in her own life and her desire to support them going forward.

(Or, to take another example, my parents were actively involved in the [local county] homemade music society when I was growing up. It didn't have any financial support or subsidies but the building that it used for practices and concerts was owned by the parks department and was later closed which ended the concerts.)