I had been pondering the question “is it immoral to vote for Trump?” Of some people who will do so, we can safely answer “Yes”: anyone who is motivated by the cruelty he seeks to impose on others, who relishes the idea of families being upended, deported, who takes pleasure in anticipating the pains of others, is immoral. But we are reminded to not lump all probable Trump voters into this category. I get frustrated by columnists at the Times who say that, well, some people have it really hard economically, so who can blame them, and economist-me thinks “I can blame them! They are about to vote for something that will, by their own metric, make them and their fellows worse off!”. But then I read something like this post by Gabriel Kahane and think, “not so fast…”. Can I find some sympathy for people who I think are making a terrible mistake?

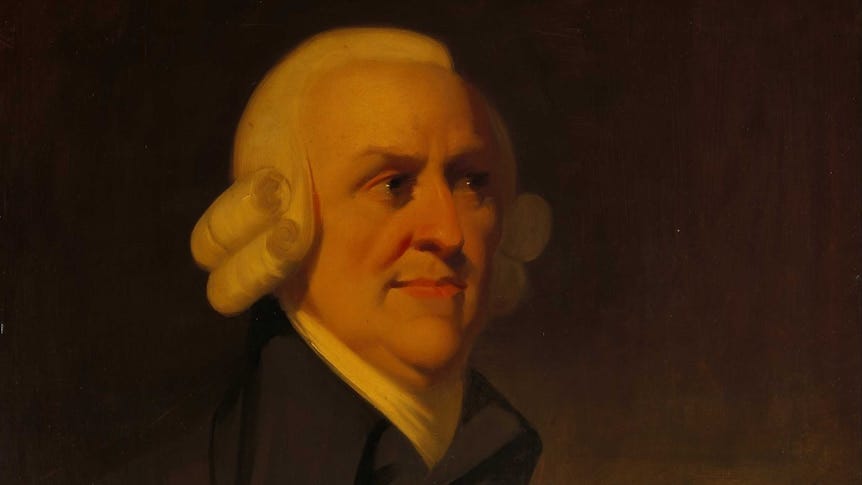

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (TMS) was published in 1759 - you can read it online here. (I have the “Liberty Classics” paperback, from my student days, when it was remarkably cheap.) Adam Smith was 36, Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, and TMS was his first book. It was drawn from his lecture notes; in my edition of the book I am told he would lecture to a class of about ninety fourteen- to sixteen-year olds (a reminder that teenagers can handle big ideas if done right), and that the way to read Smith is to imagine him in front of the class, trying to keep these lads interested.

It was very well-received in the day - his friend David Hume praised it, as did Edmund Burke. But it is not much cited these days - scanning my shelves of modern classics in moral theory by Hare, Nagel, Scanlon, Parfit, Nagel, he barely warrants an index entry. Even in the most-read book on ethics in the first part of the twentieth century, Henry Sidgwick’s The Method of Ethics (7th edition, 1907), Smith is mentioned only in passing towards the end of the book, in a section on the “morality of common sense”, which was supplanted by what was thought a more methodical system of utilitarianism.

But I’m drawn to “common sense”, if by that we mean what we see when we go outside. Smith begins his more famous book, The Wealth of Nations, by describing a pin factory. For Smith, ethics begins in observing human nature, and in particular about how we react to the pain or pleasure in others. Reflecting upon this sympathy, we realize that others have perhaps similar reactions (we cannot know for sure their exact nature) when they observe us. And so begins a recursive process of people seeing one another, sympathizing (or sometimes not) with one another, of caring about how we are perceived, and so on. And this is the basis of ethics - how we think about other people, how we treat other people.

TMS begins:

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it. Of this kind is pity or compassion, the emotion which we feel for the misery of others, when we either see it, or are made to conceive it in a very lively manner. That we often derive sorrow from the sorrow of others, is a matter of fact too obvious to require any instances to prove it; for this sentiment, like all the other original passions of human nature, is by no means confined to the virtuous and humane, though they perhaps may feel it with the most exquisite sensibility. The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it.

We begin not with trying to define the right or the good, but with our sympathy, for our friends and families, our casual meetings, for the rich and famous, for the homeless, and to us unknown.

I am taken with this approach, and so expect posts for the next while as I read this book, try to learn something from it, and, who knows, maybe revive some interest in it.