Suppose you had a friend who liked butterflies, and your friend had been out on a day trip to look for them. She came back, and you asked how it went. She answered, “the first meadow we went to was nice for butterfly watching, but the second was even better: the butterflies were more diverse.” What do we think she meant by this? It’s unclear, because diversity operates on more than one dimension. It might be that the second meadow had a greater number of different species than the first. But what if while the second meadow had more species, ninety-five percent of the butterflies were all of the same species, with the others, in tiny numbers, making up the other five percent? Maybe the species in the second meadow were more evenly distributed. But what if that even distribution was across only a handful of different species? What we need here is some sort of measure that could capture these different aspects of what we could then call diversity.

Biologists in the 1940s started trying to come up with a solution. In a 1943 paper by Fisher, Corbett and Williams, they take on the problem of creating an index of diversity for butterflies in Malaya (that’s a plain lacewing pictured above). This was refined by Simpson in 1949 in Nature. In the end, what was settled upon in contemporary science was, with variations in details but with the same core idea, something like this, (taken from a paper I published in 2008):

This is often called the Blau index, where diversity - D - increases with the number of groups or species, and with how evenly they are distributed.

I am not a statistician (not a very good one, anyway), and my paper “A Note on the Use and Misuse of the Racial Diversity Index” is neither about arts policy nor economics. I am not a greatly cited author, but this ended up being the most cited thing I ever wrote (and continues to be so on an annual basis). Here is how I came to write it:

I was attending a workshop presented by a visiting speaker in public administration. I can’t fully remember the details, but it was something about the performance of agencies in government and the racial and ethnic diversity of staff and management. If you go on Scholar and look up “diversity” + “board performance” you will find thousands of articles that were much like the workshop I attended. Anyway, the presenter measured diversity with the Blau index as I describe it above. And it struck me as a strange thing to do. Because the use of this index makes two claims about race and ethnicity in teams.

The first claim is that race and ethnicity matters: if you thought race and ethnicity did not matter for the performance of the agency, then why bother including a diversity measure at all? Why not just consider the education of members, length of tenure in the job, incentive pay for performance etc etc when it comes to agency performance?

The second claim is that, in a sense, race and ethnicity does not matter. Consider: the Blau index of diversity will give precisely the same score to a management team that is eighty percent Black and twenty percent Latino as to a team that is eighty percent White and twenty percent Asian-American. Diversity of race and ethnicity matters, but not the actual race and ethnicity.

For trying to document the diversity of butterflies on an offshore Malaysian island, the Blau index might be just fine. But social science researchers are studying the interplay of people from different races and ethnicities precisely because they think there are important differences between them, say, for example, because they think that historically some groups have been excluded from various positions in management and governance, or because people from different races and ethnicities will bring different perspectives to discussion of strategy. But then wouldn’t it just make better sense to ask of your data sample: “what proportion are from historically excluded people?” Why diversity?

In the early 1970s, Allan Bakke applied for, and was denied, admission to the medical school at the University of California at Davis. The school used a point system to rank candidates, based on GPA, GPA in science courses, the MCAT, letters of recommendation and so on. Bakke was a white man. The school also had a separate “special” admissions program, directed for the most part at recruiting students from racial and ethnic minorities, and the school ensured that a certain number of students from the special program would receive admission. Bakke claimed that his admission scores were higher than that of some of the students admitted through the special track, and that this violated his Fourteenth Amendment rights to equal protection, California’s state constitution, and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which among other things prohibits discrimination on the basis of race. The case made its way to the Supreme Court in Regents of the University of California v Bakke (1978).

The judgment is a complicated one, and I won’t try to give a detailed summary. In brief: It was held that the UC admissions system went too far in terms of racial quotas, and Bakke ought to be admitted to the school (he went on to graduate and become an anesthesiologist). But, schools were still allowed to consider the race of applicants as a factor in admissions.

For our purposes here, this is a long extract (with footnotes omitted) from the decision announced by Mr. Justice Powell:

Physicians serve a heterogeneous population. An otherwise qualified medical student with a particular background -- whether it be ethnic, geographic, culturally advantaged or disadvantaged -- may bring to a professional school of medicine experiences, outlooks, and ideas that enrich the training of its student body and better equip its graduates to render with understanding their vital service to humanity.

Ethnic diversity, however, is only one element in a range of factors a university properly may consider in attaining the goal of a heterogeneous student body. Although a university must have wide discretion in making the sensitive judgments as to who should be admitted, constitutional limitations protecting individual rights may not be disregarded. Respondent [Bakke] urges -- and the courts below have held -- that petitioner's [The University’s] dual admissions program is a racial classification that impermissibly infringes his rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. As the interest of diversity is compelling in the context of a university's admissions program, the question remains whether the program's racial classification is necessary to promote this interest. …

The experience of other university admissions programs, which take race into account in achieving the educational diversity valued by the First Amendment, demonstrates that the assignment of a fixed number of places to a minority group is not a necessary means toward that end. An illuminating example is found in the Harvard College program:

"In recent years, Harvard College has expanded the concept of diversity to include students from disadvantaged economic, racial and ethnic groups. Harvard College now recruits not only Californians or Louisianans but also blacks and Chicanos and other minority students. . . ."

"In practice, this new definition of diversity has meant that race has been a factor in some admission decisions. When the Committee on Admissions reviews the large middle group of applicants who are 'admissible' and deemed capable of doing good work in their courses, the race of an applicant may tip the balance in his favor just as geographic origin or a life spent on a farm may tip the balance in other candidates' cases. A farm boy from Idaho can bring something to Harvard College that a Bostonian cannot offer. Similarly, a black student can usually bring something that a white person cannot offer. . . .

"In Harvard College admissions, the Committee has not set target quotas for the number of blacks, or of musicians, football players, physicists or Californians to be admitted in a given year. . . . But that awareness [of the necessity of including more than a token number of black students] does not mean that the Committee sets a minimum number of blacks or of people from west of the Mississippi who are to be admitted. It means only that, in choosing among thousands of applicants who are not only 'admissible' academically but have other strong qualities, the Committee, with a number of criteria in mind, pays some attention to distribution among many types and categories of students."

In such an admissions program, race or ethnic background may be deemed a "plus" in a particular applicant's file, yet it does not insulate the individual from comparison with all other candidates for the available seats. The file of a particular black applicant may be examined for his potential contribution to diversity without the factor of race being decisive when compared, for example, with that of an applicant identified as an Italian-American if the latter is thought to exhibit qualities more likely to promote beneficial educational pluralism. Such qualities could include exceptional personal talents, unique work or service experience, leadership potential, maturity, demonstrated compassion, a history of overcoming disadvantage, ability to communicate with the poor, or other qualifications deemed important. In short, an admissions program operated in this way is flexible enough to consider all pertinent elements of diversity in light of the particular qualifications of each applicant, and to place them on the same footing for consideration, although not necessarily according them the same weight. Indeed, the weight attributed to a particular quality may vary from year to year depending upon the "mix" both of the student body and the applicants for the incoming class.

This kind of program treats each applicant as an individual in the admissions process. The applicant who loses out on the last available seat to another candidate receiving a "plus" on the basis of ethnic background will not have been foreclosed from all consideration for that seat simply because he was not the right color or had the wrong surname. It would mean only that his combined qualifications, which may have included similar nonobjective factors, did not outweigh those of the other applicant. His qualifications would have been weighed fairly and competitively, and he would have no basis to complain of unequal treatment under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Others might choose a different date, but it seems to me the Bakke decision marks the birth of capital-D Diversity in the United States: schools could not use strict racial quotas in admissions, but race could be a factor among others, since schools have a “compelling interest” in a diverse student body. Over the decades that followed, Equity and Inclusion were added to Diversity as compelling interests, and we obtained the familiar DEI acronym, for which there had been murmurs of complaint over the years, but which at time of writing has become something of the root of all evils.

What’s the story?

One story (there are a few) arose in the study of management: does diversity improve board or management performance? Here is the abstract from what I think is a pretty representative paper, by Evans, Kuenzi and Stewart, Public Administration Quarterly, 2024:

Nonprofit boards receive plenty of advice about what they “should” do, but many fail to heed the guidance—perhaps due to limited resources, a failure to prioritize, or not realizing the critical linkage between board performance and organizational performance. This research examines diversity in board membership by linking board diversity to organizational performance. We utilize data from a large, representative national survey of nonprofit executives in the United States to examine the diversity of nonprofit boards in terms of visible diversity and inclusive behaviors and practices. Using regression analysis, we find diverse boards have more inclusive governance practices, and board diversity practices are positively related to nonprofit performance. These findings offer fresh evidence about why diversity matters relative to how boards function and their impact on fulfilling their organizational mission. This research contributes to how we think of diversity and inclusion in the nonprofit sector and why it matters beyond representational value.

What is the relevant aspect of diversity in management studies? We can collect data on gender, race and ethnicity, and age, and these are typically the defining features. Can different perspectives help? Probably: a board whose members were all in their twenties, or all in their sixties, will likely be missing out on valuable information about customers/audience, or what issues are most salient in attracting and retaining good employees. A mix of men and women will be helpful in this regard as well. What about race and ethnicity? My idiosyncratic take - and I fully recognize this is nothing more than a personal view - would be that this matters less than the other factors: a twenty-three year old woman and a fifty-nine year old man will likely have differences in how they see the environment in which the firm operates, and so can help each other correct for blind spots, and that beyond that race and ethnicity becomes something of a smaller factor. Put another way, in terms of differences in knowledge and outlook, the race of my twenty-three year old woman and fifty-nine year old man is of lesser importance than other differences between people.

For example, do we get better ideas (or “creativity”) from people who are “diverse” in terms of with whom they interact? I used to enjoy introducing my students to this work by sociologist Ronald Burt. In a nutshell, here was his experiment (I’m glossing all the details, obviously): Take a very large firm, and ask each person working there to suggest, briefly, one single idea that would improve the company’s performance. Then have a team of management, plus people knowledgeable in the field but outside the firm, evaluate the proposals. Who had good ideas?

Suppose Amy works there, and we ask her “on a regular basis, who do you have the most interactions with?” She answers, “Bob, Charlie, Doug and Emma.” Then we ask Bob the same question, and he answers, “Amy, Charlie, Doug and Emma.” Then we ask Charlie, who says, “Amy, Bob, Doug and Emma.” And similarly for Doug and Emma. In other words, we have something of a closed loop. And their ideas will be a bit ordinary.

But suppose Frida says, “I interact most with Gord, Harry, Isobel, and Jake.” And Gord says, “I interact most with Frida, Kaitlyn, Larry and Mike.” And Harry says, “I interact most with Frida, Nelson, Ollie and Pat.” And so on. On average, Frida is the sort who will have more interesting ideas: her circle of close contacts all have very different circles themselves. The closed-loop group (and I have observed this myself in workplaces) get very good at doing routine tasks efficiently - they work as a team, know what each person’s strengths are, and blend. If you have done choral singing, you know that a choir of even very talented singers sounds a bit of a mess at first - the singers have to learn to blend with one-another (I used to row, typically in a quad scull, and the same thing was true - effective rowing requires perfect synchronization, and that gets better over time with the same crew). But good new ideas need something else, a spark of “I was talking to this person the other day, and they were talking to this other person I’ve never met, and apparently this other person said…”

So, Burt is talking about a kind of diversity, but not one based on the immutable characteristics of people. Instead, what do they do now, who do they know, who do they listen to, how wide is their network? If I were to be appointed to a board, what would matter is less my race, sex, or age, as much as what I have learned over time, what am I able to see or hear about in various other firms.

I was once appointed to the governing board of a division of legal aid (in the US, the public defenders office) precisely because I was not a lawyer, and could bring something from the outside.

So maybe the key to diversity and how it affects firm performance is less about demographic categories, but something else.

Roger Fry, in his essay on aesthetics, said that in a work of art:

… the first quality that we demand in our sensations will be order, without which our sensations will be troubled and perplexed, and the other quality will be variety, without which they will not be fully stimulated.

And that is where diversity matters in the boardroom, in the management team: there has to be order, a shared vision of what the goal of the firm (whether commercial, nonprofit, or public sector) is, and variety such that individual members remain stimulated, challenged. A management team cannot be so diverse that there is no agreement on the fundamentals, on the goal. In recent years we have seen conflicts in arts organizations, often arising where politics intersects (or could intersect) with art, where the conflict is between different individuals within the organization having quite different conceptions of what the organization is meant to be doing. Is it a place for political activism or not? And that is a diversity that can be ultimately destructive.

In the world of business and government (I’ll get back to universities later), DEI in hiring and policy formation is now facing intense backlash - every guest on right-wing media has to mention DEI at least once as the cause of ships colliding with bridges, planes falling from the sky, or cities built in a desert facing hurricane winds having forest fires. DEI = incompetence:

Ms. Gabbard isn’t being serious, any more than dubbing herself MAGAQueenUSA is serious: Over ninety percent of commercial airline pilots in the US are male, making it what must be, among skilled professions not dependent on the physical strength of men, about the most male-dominated profession there is, and the proportion of these pilots who are white is much greater than the population as a whole. Has she experienced many black, female pilots? I don’t think I ever have. She is, as the kids say, trolling, and aware that, as we advise our students going onto the job market (and she is, as I write this, heading for the interview stage), you are always “on.”

So is Jesse Watters, who says in this clip “This is the leadership of the LA fire department; I sure hope they know what they are doing.”

Well, why wouldn’t they? Because, we are meant to gather, these are “DEI hires”, and, ultimately, “DEI promotions,” and we are assumed know that because they don’t look like what he thinks a fire chief is supposed to look like.

In the mind of these critics, America has a million Allan Bakke’s, brilliant talents, being wasted in dead-end meaningless work while the DEI’s get hired and wreak havoc. I don’t know if they believe that in some golden age America was a true meritocracy, that we lost through misguided public policy, or if it remains the star which we might not yet have reached, but is the ideal from which DEI diverts us. About the man they just elected president, I don’t think anyone could say with a straight face, “Just look at his choices for cabinet; now there is someone committed to hiring only on merit, the best and the brightest.” Though I might be mistaken about that.

And finally, to college.

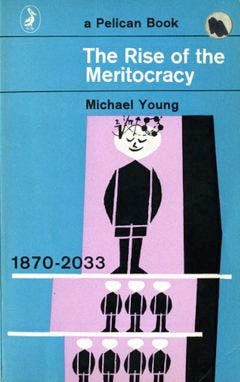

Michael Young published The Rise of the Meritocracy in 1958, and it is a brilliant, astonishing piece of forecasting. The book is written as if by a writer from close to our time (2033!), looking back on how a commitment to hiring only on the basis of “merit” worked out (in days of yore academics sometimes wrote entertaining books…). He had two principal predictions.

First, in practice, we would end up relying on a single means to measure “merit”, since it is an already available sorting mechanism: education. Merit = good at school. Colleges select the top high school students, graduate and professional schools select the best students from top colleges, and firms in the private and public sector evaluate candidates on where they went to grad school or law school. In a time of great wage inequality then, there is a fierce battle to attain the highest academic credentials. In the college town I live in, parents - and I am writing about friends, whom I love - are simply bonkers when it comes to obsessing over where their sons and daughters will go to college (in my home and native land to the north, there is less wage inequality, and much less of a hierarchy of universities, and the best universities are really big, taking in thousands of freshman each year, so you just don’t tend to see this nearly as much).

Second, Young thought that the people who did not come out on top in the educational sphere would grow tired of being told “well, if only you had studied, maybe you would have attained some merit - your dim economic prospects are your own fault.” And they would revolt, against the “elites”, against the preferences given to graduates of top schools. Politicians who want to gain the votes of this group are in a bind, since many of them attended Ivy League schools. They finesse this by saying “I was smart enough to get into Yale, but don’t worry, I didn’t like it, and you shouldn’t try to send your kids there anyway” (omitting that they will advise their own children that they really do need to go to Dad’s old school).

Who gets in to selective universities is not about who will get to take classes from the best professors (or their graduate students) and read the best books. It is about who will get stamped with “very high merit” as they graduate and venture into what we call a “meritocracy.”

What is DEI in universities about then? We are seeing its end in American universities: my state legislature has a bill before it that would eliminate the use of race as a consideration of any sort in admissions or scholarships, ie as a factor that could be used to enable greater diversity, and I expect the bill will pass.

In the end, the Bakke decision left university policies in an unsustainable limbo, being allowed to pursue “diversity,” including in race and ethnicity, but not by too much, such that it would resemble the quotas that were used by the University of California at the time. Opponents of taking race into account in admissions and other benefits said, well, it is simply unfair to do that, it is impossible to do it without disadvantaging other students. And in the end, the Supreme Court agreed, in 2023, overturning Bakke with Students for Fair Admission v Harvard.

I am divided on this. I guess I am lucky to have retired before any committee asked me to write a personal DEI statement, though if I had been asked I probably would have said that I have always tried to be E and I to all my students, in all their individuality, which goes far beyond race, gender, sexuality. And as for D, I teach the students I get on my course roster - who they are was decided elsewhere.

“Diversity” in DEI was always something of a fiction: critics were correct that it ultimately came down to trying to increase the number of students from groups that were traditionally excluded, and that this meant there were bound to be some Bakke’s (or Asian-American applicants) who saw themselves as thus being put at a disadvantage. It was never really about the value of diversity.

But that said, I don’t think it is wrong to do that. Groups that have long been excluded from various positions in society, and as such have few role models (or parents) in those positions, could and should benefit from special considerations. After all, it is in my lifetime that there were violent protests by college students against the integration of their campuses. There has to be something more done about this than just saying “sorry about that, you’re okay to come here now, really.”

Should the policies that have come to be known as “DEI” go on forever - scholarships or pre-college programs that target groups traditionally underrepresented in college? I hope not; I might not be around to see it, but the day when the US can say “all right, I think we are at a point where there are no longer differences in the status of racial and ethnic groups such that we need remedial policies any more” will be a good one. It would also be great if college, especially selective-admission college, simply didn’t matter as much as it does in terms of opportunities and offices, where people didn’t care as much that you went to Brown instead of Kansas State.

But we are not there yet.

When Claudine Gay disgraced herself and her institution in front of Congress in late 2023, she invited scrutiny of her career. The wider world learned that her publication record was scanty and riddled with plagiarism that would have gotten any Harvard student thrown out of school. Furthermore, she had been instrumental in damaging the careers of academics who published findings that defied progressive assumptions, including the economist Roland G. Fryer, Jr. While Gay was forced out of the presidency, she continues to work for Harvard for a salary of $900,000 per year.

Irritation about DEI does not hinge on what a firefighter is supposed to look like. It is recognition that if you tick certain identitarian checkboxes and espouse certain beliefs, you will rise to the top of your profession and remain unaccountable even if you are incompetent and evil. You may lie with impunity and harm the people around you, and the institutions will protect you. Understandably that attitude is widely unpopular, which explains the popularity of the president-elect and the unpopularity of the institutions.

In 2022 the American Alliance of Museums commissioned a demographic study that found that women comprise 76% of intellectual leadership at the museums. Women museum directors outnumber men two to one. This did not spark a call for parity. The talk about representation is empty. The policies do not achieve diversity, equity, or inclusion in any meaningful sense of those words. Every time they've been studied, workplace diversity trainings have been found ineffective or deleterious. People perpetuating DEI policies evidently will continue doing so until they're stopped by legal force or defunding.